Nationalité: Immigré pt. 2

A translation of director Sidney Sokhona's 1976 Cahiers du Cinéma interview

On the occasion of Anthology Film Archives’ online presentation of Sidney Sokhona’s remarkable film, available to stream through this Saturday, it’ll be Nationalité: Immigré week here. Below is the second half of my translation of the long interview Sokhona gave to Serge Daney, Serge Le Péron, and Jean-Pierre Oudart as part of the magazine’s dossier on the film in issue no. 265. The first half can be found here; I’d gently recommend reading that first, as certain things below—the very first question, for example—will seem somewhat obscure read out of order. (Again, my apologies in advance for any infelicities of translation; as this half is a bit more complicated at times, I’ve included the original language at a number of spots where my meager autodidact’s French was defeated.) A translation of Daney’s essay on the film can be found here. I’ll have some brief thoughts of my own tomorrow.

Cahiers: That’s obviously not the kind criticism you would have directed at either the official left (the PCF, etc.) or humanitarian organizations.

Sokhona: Not at all. When I’m interested in something, I bring it up. In the film, I never bring up the PCF or the CGT. Why? Because to me, these aren’t people who can be reformed. While inside the extreme left, there are people who are starting to see things from another angle. At the level of the Party, it’s very different. That for two years [of the strike], we didn’t see anyone from the Party, not a single time, what’s there to even say: that an organization that huge, that powerful, ignores immigration… While the extreme left, they made errors, but they intervened all the same, and that’s what counts.

Cahiers: Our impression is that the shot of the guy in the chair, it simply says: his discourse is suspended, it’s an open question. That doesn’t mean it’s canceled, ridiculed, rendered obsolete. It just means that it’s being placed in parentheses.

Sokhona: Right.

Cahiers: There’s something else here, for example, the fact that you film a marabout. For the people we’ve discussed the film with, it wasn’t an ideal thing to film because “we know” that there are marabouts, the role they play, etc., but to say it or to film it only amounts to dividing the immigrants. But the fact is, not so many people really know and anyway, there's a difference between knowing and seeing.

Sokhona: Yes. It’s a very serious problem. Because let’s say we’re going to tell an immigrant that we’re going on a rent strike, or a strike at the factory or someplace else… well, that poses problems, very specific problems, to him. For example, the marabout. I showed him because there are loads of them in Paris at the moment. Even in the neighborhood bulletins [les annonces de quartiers], we find photos of marabouts who arrive every year from Africa to France, so that they can go on afterward to Mecca. And it’s the workers who, from Mecca, get him back to Africa! So there are these people who come here and leave after three or four months with four or five million francs, meanwhile, there are workers who live here six or seven years [without making this much], who themselves have family in Africa who dream of going to Mecca. But the marabout is so imposing that people give him money while their families are starving. There are so many problems like this, and even among politically conscious Africans there’s a certain kind of conformity: we fall in line [on copie]. Why? Because someone else gave 500 francs to the marabout, so I had better as well. And if I haven’t got 500 francs, I’ll borrow them. How’s it possible to enter into struggle with problems like this nipping at your heels? That’s why I show the marabout. But there’s also the problem of castes. There are people in France today who are treated like slaves: of two guys who go into the factory together, even if they do the same work, one also has to do the cooking while the other doesn’t. We notice this with literacy, for example. There are people who wanted to go to school at night, but they were obliged to be in the kitchen. So then, they arrive two hours late. And the rich, they don’t give a fuck about this at all. All of these problems, which are specific, aren’t yet clear within the framework of immigration. No doubt, we can say, as the far left does, that “all this isn’t serious, these aren’t fundamental problems, the essential is the struggle against capitalism” and so on. However, it’s plain that these problems hold people back from moving forward.

Cahiers: But do you think that your film can help such dogmatic people to reflect, to change their practice?

Sokhona: There are people who saw it and said to me, “Your film produces division among the workers.” And I said, “How?” They told me, “You show the marabout like that, without explaining politically why he came to France” and so on. This kind of response allows me to understand how they were able to make such errors: if they see the marabout in the same position as the workers who are obliged to give him 100,000 or 300,000 francs for this or that, if they consider the two of them, the marabout and the worker, as proletarians capable of struggling side by side, well, then I don’t think we’re going to get out of this shit, ok? And there’s another type of question which has been posed to me by leftists who expect a militant film with slogans, with certain words—colonialism, neocolonialism, etc.—which aren’t found in the film. I say that the immigrants don’t give a fuck about being given the definition of colonialism, of neocolonialism, etc. What I do in the film is show precise situations, which they can grab hold of like a ladder and climb until they see how, and by whom, they are exploited. And it’ll be clear. Otherwise, we keep coming back to the same theses: mobilize the people against a certain bourgeoisie, who’s never very well defined; against the bosses at the factory, without taking into account the fact that the workers spend half their pay on useless junk [sans tenir compte du fait que les travailleurs dépensent la moitié de leur paie pour des trucs qui n’ont rien à voir avec ça]... It’s very important to put all that to the side. Ok? Otherwise, this critique that I focus on there, in the sequences of the guy in the chair, I didn’t want it to go beyond this setting, and I certainly didn’t want others to redirect it to different ends. I made this critique so that they would start to ask themselves some questions about the immigrants they’re going to encounter, so that they’ll stop thinking that they understand the problems of immigration better than the immigrants do themselves. Just like the question of racism, they have to look at it differently. For a leftist, a worker who says “dirty n*****,” is necessarily someone to condemn, someone who’s gone over to the other side. But for us, we live with this, we eat with this, and instead of condemning, we think we have to start to get to the bottom of why they react like this: is this how they were born? is it possible that they will change? But also why do the bosses at the factory say “Monsieur” instead of “dirty n*****,” even though they pay an immigrant three francs less than a Frenchman?

Cahiers: The film is opening now in 1976. In what context does it arrive? Where are we today, from both the immigrant side and the French side, regarding this question? What is the thinking regarding the place of immigrants in the struggles?

Sokhona: No doubt, there are demands common to both the French and the immigrants. But these can only develop with a clear base, one where the immigrants’ problems are specified. This is the base of everything. The film was begun around 1972-1973. Today we raise the question of immigration as such. We have to take into account that today the issue is different: unemployment; the fact that immigration has been halted; the fact that since last year the residence permit [carte de séjour] requirement has been imposed on Africans coming from Senegal, from Mali, which wasn’t the case before; the fact that police control will be much more severe than it was previously; the fact that immigrants are housed in Foyers managed by the Prefecture, that to enter you need three photos, a visitation card from the Prefecture; that the Foyers are under surveillance [sont fliques], etc. We hold immigrants in the fire even more today than we did yesterday. So there’s an immediate question that we’ve done everything so far to avoid, that of political rights, which means we accept all this. This is the question raised, for example, by the immigrants who recently went on strike at Sonacotra. They’re no longer simply demanding a new foyer, they’re questioning everything. It’s from these new questions that we can define the grounds for solidarity with the French. The question that arises at this level is to see whether immigration is capable of expressing itself as a force. This entails two levels. Does immigration constitute a force? And does this force represent anything within the context of French industry [production française]? If so, it’s possible to struggle. How? By defining themselves as immigrants on the basis of problems they know better than anyone, but also on the basis of their necessity to national industry. This force has to be expressed politically. Today a problem emerges: to build unity between the immigrants themselves. Once that happens, a force will be found which is capable of engaging in struggles, a force which the far left can really get behind.

Cahiers: At the moment that you, an immigrant worker, make a film, the question that emerges is the following: what images do I make of my side? And to show them to whom? Something like this problem emerges at every moment of the film.

Sokhona: The film is aimed at immigrants (or potential immigrants), more than it is toward French people. This comes from the very fact that I think the important problem, at the present moment, is to arrive at unity between the immigrants, which could then open the way for a bond with the French working class.

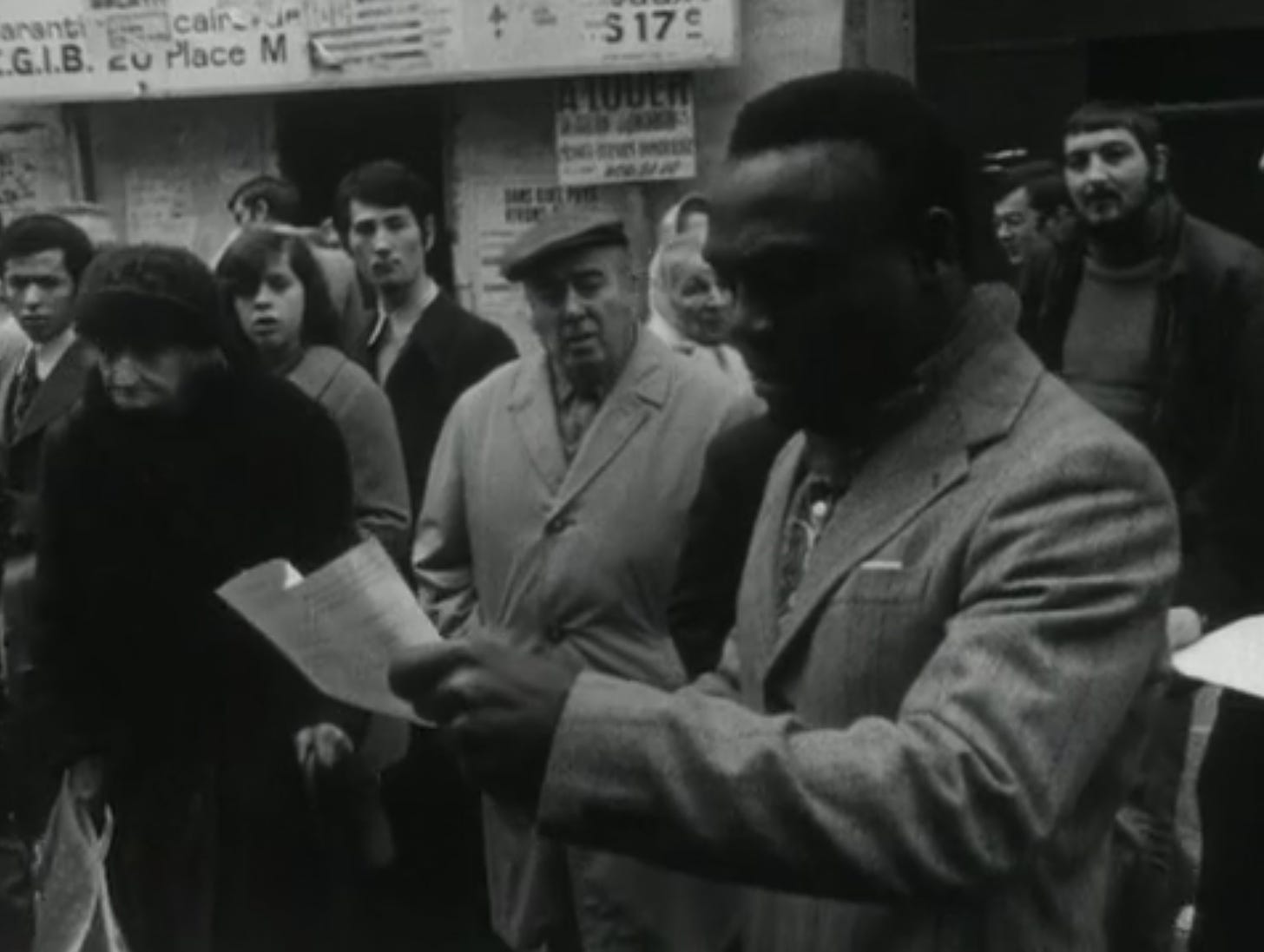

In the images, what shows that the film is intended for the immigrants before anyone else, is that I don’t insist on the images of the Barbés or the Foyer [Riquet]. I show them because this is the life of the immigrants, but don’t insist, because they know all that.

Cahiers: So could we say that your film has a three-part audience? The French, the immigrants who know the situation, and the immigrants yet to come?

Sokhona: First, there are the immigrants who are already in France, who are the main audience [les destinataires privilégiés]. Why? Because there are plenty of foyers which have never known a strike. The film, and discussion after the film, can make them think about a lot of things. And there are potential immigrants, and I’m going to explain why. Whether we’re talking about North Africans or Black Africans, when they return home on vacation, they see the fact that they live in France under these conditions as a mistake [ils ressentent comme une faute le fait de vivre en France dans ces conditions]: they’ll never admit that they live in the slums. And add to that the propaganda made there [i.e., in the foyers], aimed at the arrival of other immigrants. If the film could be seen by the people there, an account of that reality would already be rendered for them. As for the French people who are going to see the film, I think it’s very helpful.

Cahiers: You said that you wanted to make a fiction film. However, your main fiction is very simple: there is a figure who traverses all the situations, all the shots, and this figure is played by you. There’s a lot of discourse in the film which is extremely precise and anchored very concretely (i.e., spatially), but you seem to traverse all of it. Initially, you appear as one immigrant among others and then, at the moment the Foyer Riquet appears, it’s you who comes to revolt, to politicize things…

Sokhona: It’s true that this is fiction, made from constructed situations. But all the figures that we see in the film are playing themselves [ont leur répondant dans le réel], they exist. I wanted to make a fiction film because in documentaries, everything depends on the sound. And among the immigrants, this is really imposing, really heavy, particularly when it comes to the French language. In the foyer where I was, for example, there were three hundred people, but there were maybe sixteen who can read and write.

Cahiers: In general, when there’s a fiction film of this type, we see a figure who gradually comes to conscience. We see them asking questions, wavering, etc. However, in your film, there’s none of this at all: it’s entirely very concrete scenes of the relationships between people and never what is going on within the mind of this or that individual.

Sokhona: My figure plays an ordering role [Le personnage que je joue a un rôle de coordination]. There was never any question on my part of showing the dreams of this guy, nor of the three hundred people that were in the foyer (and they have them!). What I wanted was to show a given situation: we show up, leave a mark, pass on [on montre, on marque et on passe]. The figure who I play, I show him as a rebel, rather than a revolutionary. Plenty of people could have had the kind of response he does. It’s precisely the fact that one workday he sees two old men meeting in secret with a guy who’s come to manipulate them in the office that causes the tone to heighten and the situation is transformed. He says to himself, “I don’t give a fuck anymore” and so on. He revolts. But that doesn’t mean a revolution has come out of nowhere [Mais ça ne veut pas dire que c'est un révolution naire tombé du ciel].

Cahiers: Over the course of the film, you sometimes play an activist role, but you never speak up on behalf of others. You are not playing an opportunistic role [un rôle capitalisateur].

Sokhona: An important thing at Foyer Riquet was the complete refusal to be represented: for example, by electing a tenants committee. This was a real pain for the police. When they’d arrive and demand, “Where are the delegates?” We said, “Behold! Three hundred people!” It really fucked them up. And then we tried to ensure that everyone could express themselves: since we’d often criticized the far left for speaking in our place, we weren’t going to make the same mistake.

Cahiers: Can you talk a bit about the opening of the film on July 14? The initial reactions?

Sokhona: Before July 14, I met with a number of theater directors who rejected the film. I met with Karmitz, who agreed to go ahead with it as a theater owner, but not as a distributor. I had to distribute it myself. I didn’t have any money and the theater paid an advance for the print, the pictures that ran in Le Monde, etc. The opening confirmed for me a bit what I’d already thought before. What was interesting in the discussion was to see that a film is a means of action [moyen d’action—a phrase also translatable as “policy instrument,” a fact particularly relevant to Daney’s essay on the film] like a book or an article, except that it allows for better dialogue. The dialogue grew over the course of the discussion on July 14. Sometimes people introduce new information about immigration… It’s more or less what I expected from the film.